Identity in the Age of Overconsumption

FW26 marks the convergence of two opposing forces — the utilitarian restraint of FW25 and the playful rebellion that followed — with accessories serving as the bridge between function and self-expression. This report tracks how hoods and bandanas (up 15%), statement tights in color-block and printed styles, sculptural scarves (scarf dresses up 120%), and structured leather bags are transforming durable investment pieces into personalized statements. After a year of customization momentum from bag charms to DIY embellishments, FW26 accessories offer low-risk, high-impact ways to inject individuality into practical wardrobes.

Alice Clarke

"As overconsumption weakens fashion’s emotional value, identity shifts toward the maker economy, slow fashion, and more meaningful personal connections."

When we wear something, it tells a story about who we are. But the rise of ultra-fast fashion has caused a disruption in this relationship. Clothing is no longer something we grow with, mend, and cherish. We accept its obsolescence and cycle through it, swapping one micro-trend identity for the next. Over time, as we have come to terms with this pattern, clothing has lost its significance to us. Holding what is new is of a higher importance than who we are. When we are living in such a wasteful cycle, where clothing can constantly be made faster and cheaper, how do we rediscover meaning in ourselves and our wardrobe?

Why Now?

In a recent Wall Street Journal interview, 89-year-old Kay Washburn spoke of babysitting for 50 hours in the 1950s to buy her dream dress, which she wore and repaired until it physically fell apart. But today, she can order a pair of capris from Shein for six dollars without leaving her bedroom, aware that they will likely last only a few seasons. Her story is a microcosm of our current relationship with clothing, accepting its short lifespan and replaceability. As a result, we have no care or attachment in return.

Ultra-fast fashion brands have capitalised on this detachment. One example being PrettyLittleThing’s recent Black Friday sale saw website-wide discounts from forty to eighty percent, with clothing being sold for mere pennies. The time, effort, and yearning we once felt towards fashion have been replaced by the instant gratification of dupes and micro-trend pieces that break, pill, or just fall out of alignment with whichever identity we embodied for the month.

We have previously spoken about how clothing is a tool that shapes who we are. But fast fashion has made identity itself feel disposable. Personal growth is a slow process, and our wardrobes are now too short-lived to be a part of it. When we can reinvent ourselves cheaply every month, fashion becomes a form of avoidance, where we can hide behind an aestheticised version instead of confronting who we are and becoming.

The Change

Even compared to a few years ago, our relationship with clothing has undergone a dramatic change. In 2021, Vice reported on nightclub bans on athleisure, jeans, and casual wear, all styles that are now widely accepted as going-out outfits (+33.3%). This casualisation was accelerated by the pandemic and the collapse of boundaries between home, work, and rest.

We also see this through the rise of comfort and loungewear (+35.4%) and pyjamas as daywear (+12.7%) in the mainstream. Premium loungewear brands such as Adanola (+47.6%) and Alo Yoga (+32.6%) helped to turn comfort into a status symbol. Alongside this, rising living costs, loneliness, and more time spent indoors have all pushed consumers to invest in clothes that support staying home and opting for temporary and low-investment pieces for going out.

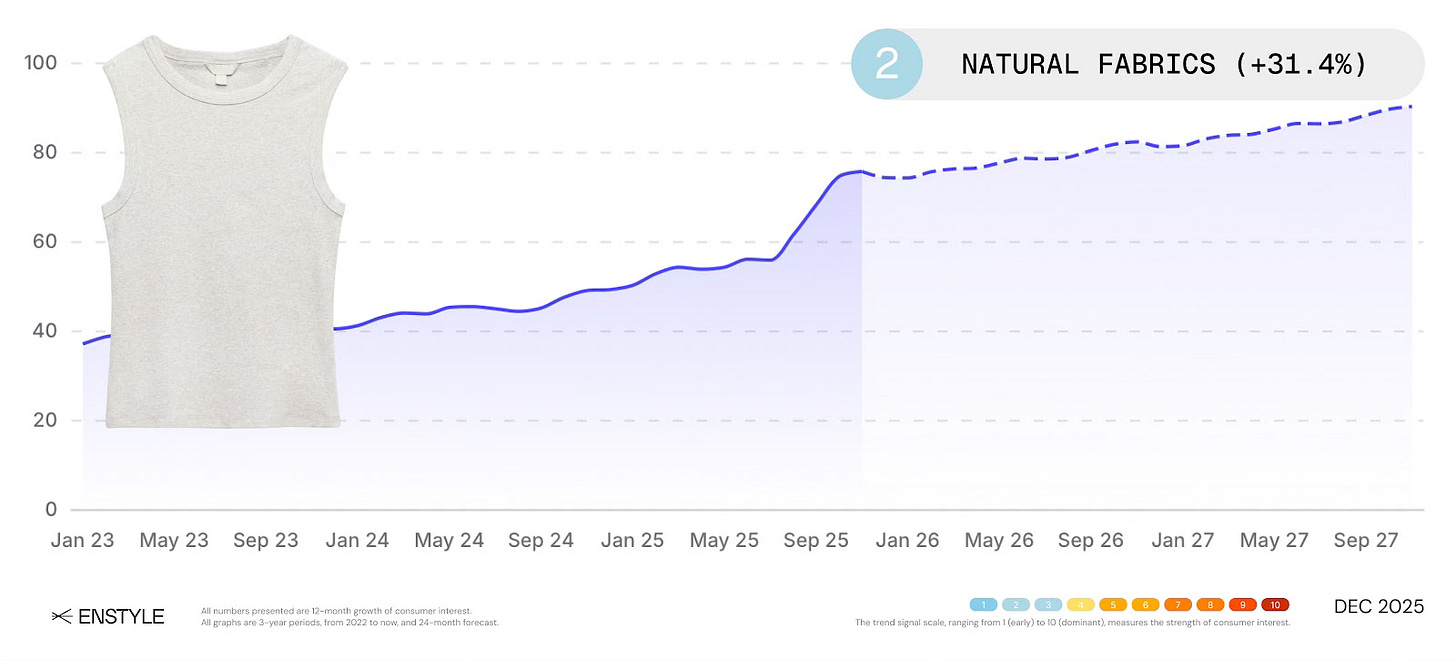

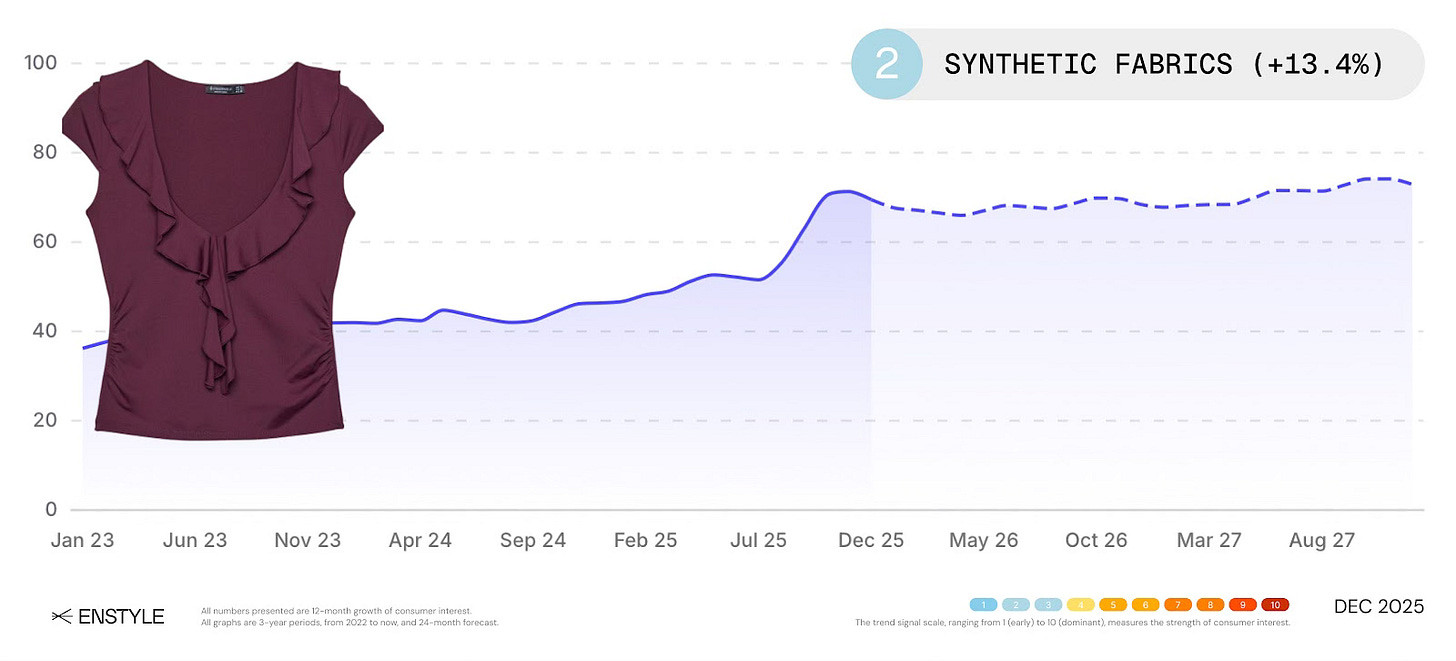

Fabrics and Consumption

This is all happening at the same time as the online demonisation of synthetic fibres. Consumers are taking to social media to purge their wardrobes of polyester (+15.8%) and nylon (+10.2%) and replacing them with cotton (+11.7%), linen (+24.9%), and wool (+6.9%), framing the swap as both chic and sustainable. Yet, this quickly becomes another form of aestheticised overconsumption, discarding perfectly wearable synthetics only to buy new fabric that aligns with a trend.

Brands were eager to cater to this trend, with brands from Adidas to Reformation, utilising recycled natural and synthetic fibres instead of creating more waste. However, this also leads to distrust through greenwashing, misleading fibre labels, and recycling claims. Making the landscape increasingly more confusing for those consumers who are looking to ‘do the right thing’.

Second-Hand Alternatives

This distrust and frustration drove many towards second-hand platforms. Vinted saw a 36% increase in sales from the previous year, and charity shops in general are seeing increases in new visitors. Second-hand shopping re-established a space for individuality, slower consumption, and an overall stronger connection with our clothing.

But these spaces, too, have been compromised. Charity shop prices have risen sharply. Retailers, including Zara and Marks & Spencer, have begun donating unsold and damaged stock directly to the Red Cross and Oxfam, which has flooded the shop floor with brand-new clothing that never needed to be produced in the first place. Online resale platforms are suffering from similar over saturation, with ultra-fast fashion crowding the search bar and turning these spaces into overflow systems of overproduction.

Where Does The Consumer Go Now?

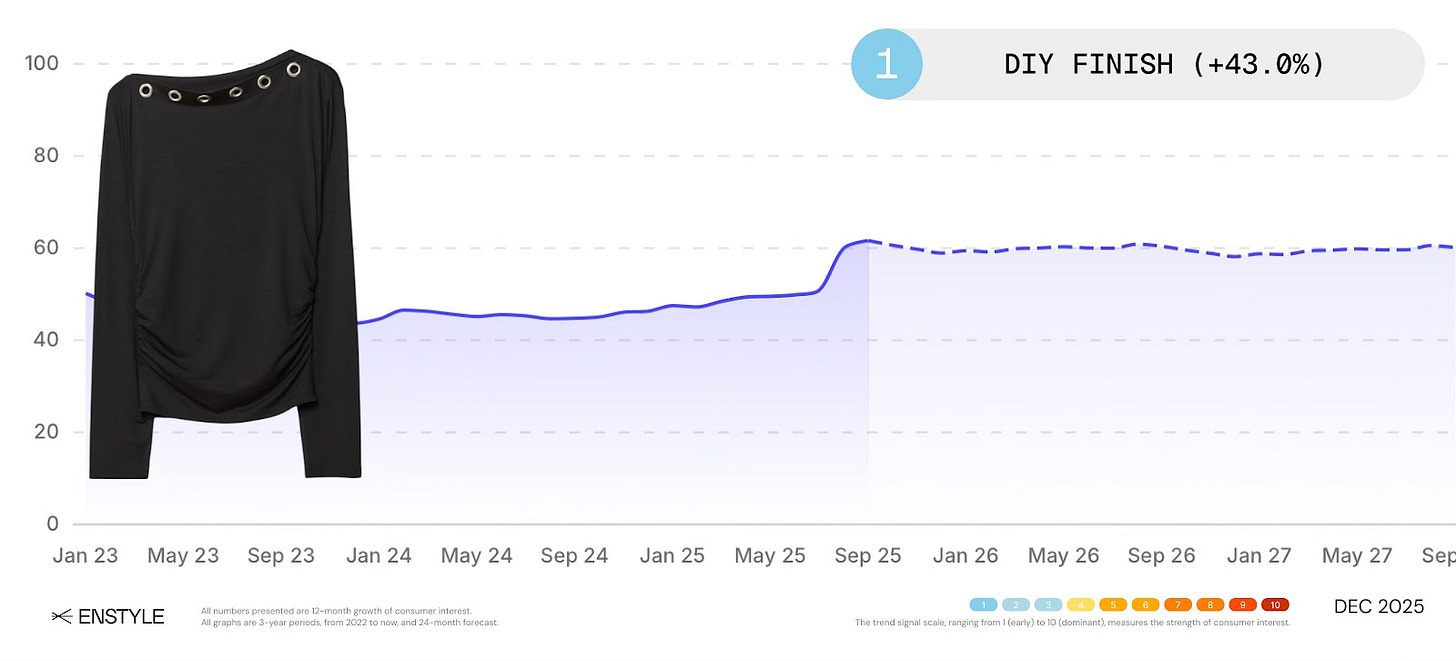

The idea of the investment piece is evolving: what was originally considered as luxury shifted to rare vintage finds, now moving towards handmade creations that require more time than money. More and more, we see consumers finding meaning through making. The value that once came from shopping is being rediscovered by sewing, knitting, mending, and upcycling. The early signs of this came from the Losercore movement, where DIY embellishments, alterations, and reconstructions became a way to build a unique identity with clothing.

Gen Zs in particular are said to be behind the recent revival of traditional hobbies, labelled ‘Grannycore’, which reflects a desire for slow living (+82.5%) and intentionality. These skills take time to master, and the perceived boringness of ‘Grandma hobbies’ is now being celebrated in a time where we are desperate for meaning and purpose.

In an interview with the BBC, the founder of PetiteKnit, one of the most popular pattern designers currently, believes that the disillusionment with consumerism is driving the rise of hobbies like knitting. Stating that when a garment takes a significant amount of time, you build a relationship with it, you don’t want to throw it away; instead, you have the desire to repair it or just cherish it for the labour it took and its sentimental value.

This label of ‘Grannycore’ fails to capture the full reality of this movement. These practices are not solitary or old-fashioned; increasingly, they are about community. Knitting meet-ups, workshops, Knittok, and online craft forums are being reinvigorated by younger audiences seeking meaning and connection to avoid growing loneliness.

Brand Response

This rising interest has not gone unnoticed by brands. Indie textile designer, Hope Macauley, began releasing patterns and wool alongside her signature hand-knit pieces a few years ago, inviting consumers to participate in the making process or create something new in her colour palette and style.

More recently, the Damson Madder x Wool and the Gang collaboration released both finished bonnets and sweaters with the matching knitting pattern. This gives consumers endless creative freedom to recreate the pieces in any colour combination they like. Although the knit’s high price faced a backlash, the collaboration suggests a potential shift of mainstream brands, offering patterns and participatory kits alongside their ready-made garments, to cater to the growing maker economy.

Where It’s Headed Next

If buying has become meaningless, second-hand is oversaturated, natural fibres are performative, and synthetic is vilified, then the consumer must find meaning elsewhere.

We see this reflected in Pantone’s Colour of the Year, Cloud Dancer, a neutral that signals a desire for less choice and visual noise, creating space to focus on what truly matters, encouraging us to find identity and personal taste beyond trend saturation.

Through skill-building and community, consumers are carving a new relationship with fashion that is personal and slow. Handmade pieces or customisations can not be duplicated, mass-produced, and are less likely to be thrown away. They allow us complete ownership to create our personal style and identity.

Whilst this space is still emerging, brands are already being challenged to adapt. Consumers are no longer falling for the greenwashing and misleading claims; they are seeking authenticity and a deeper sense of self. Leaving fashion brands to reconsider their reliance on disposability.

This rising maker economy suggests that the future of fashion can be slower and value is more significant, and the creation becomes a shared process between a brand and the consumer.

Stay ahead of fashion shifts

A monthly thread on fashion trends, planning insight, and how AI is shaping design, merchandising, and buying decisions. Written for fashion teams who want clarity, not noise.